Monopoly Capitalism

The United Corporations of America

In 1980, corporate lobbying was a fraction of what it is today. Now, corporations spend over $3.7 billion annually to influence policymakers, ensuring laws favor monopolies over working people. This allowed antitrust laws to have been gutted, allowing unchecked mergers and acquisitions to eliminate competition. Corporate consolidation since then has eroded economic opportunity, reduced upward mobility, and concentrated power in the hands of a few ultra-wealthy elites. The promise of hard work leading to financial stability and homeownership has been replaced by a system designed to extract wealth from the working class and funnel it to corporate interests.

Without aggressive antitrust action, financial regulation, and corporate accountability, the gap between the rich and everyone else will only widen. This new Gilded Age is marked by massive corporations prioritizing short-term profits over long-term societal well being. Let’s take a look at some of the biggest offenders in the U.S. that have brought the nation to this position.

Top Monopoly Offenders

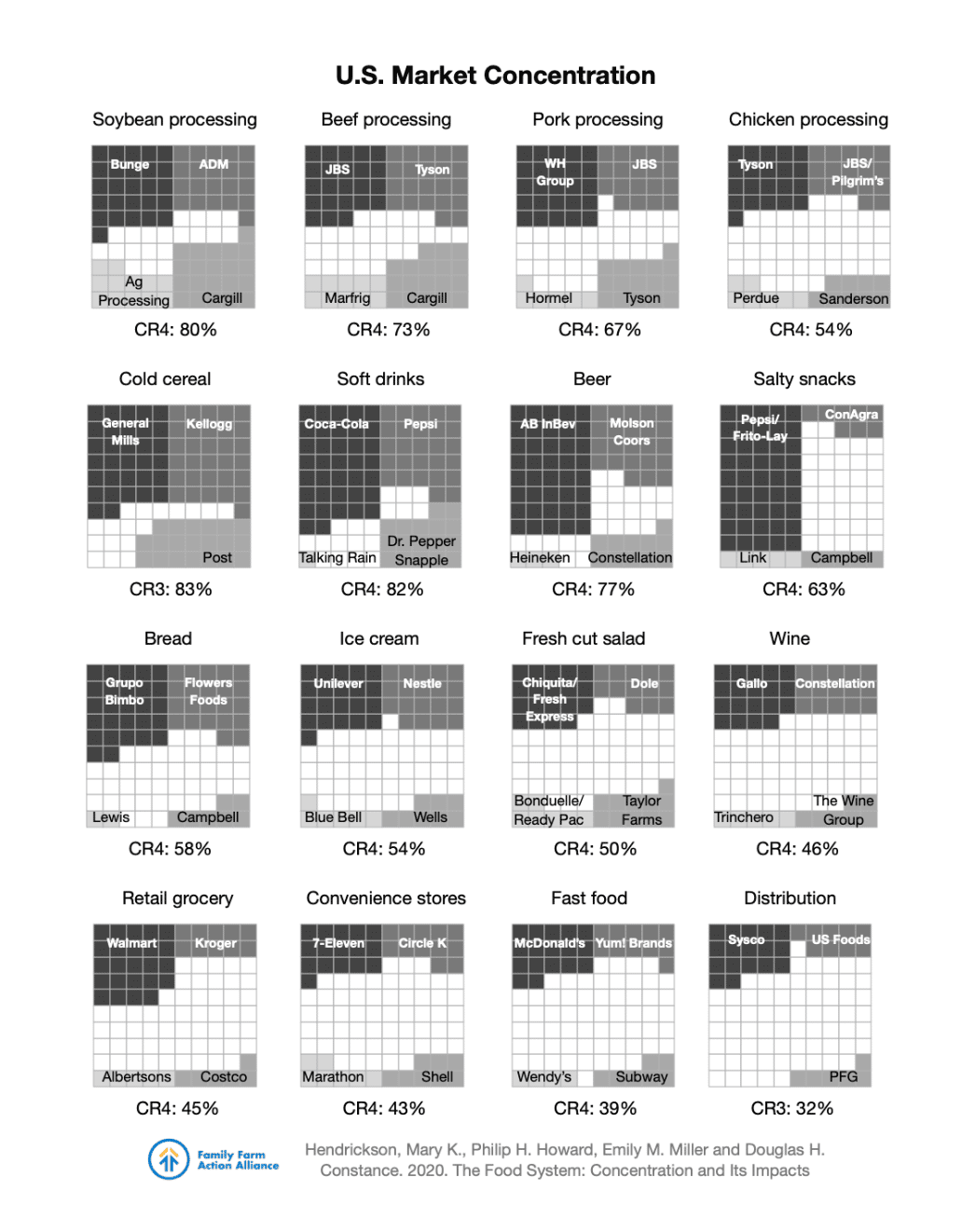

Food and Beverage

The largest five, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, Unilever, and Mondelez, control over 40% of the global food market. For example, Nestlé owns more than 2,000 brands in various segments, including 30% of the global bottled water market. These major players can dictate pricing to suppliers and use their scale to outcompete smaller brands, limiting consumer choices and driving up prices.

Beer Industry: Anheuser-Busch InBev controls around 31% of the global beer market after acquiring SABMiller. The five largest beer companies, Anheuser-Busch, Heineken, Carlsberg, Molson Coors, and Asahi, control over 60% of the market.

Telecom and Media

In 1983, 50 companies controlled 90% of the media. In 2026 the top five U.S. telecom companies, AT&T, Verizon, Comcast, T-Mobile, and Charter Communications control more than 90% of the U.S. broadband and mobile services market. This concentration stifles diversity in media, limits content variety, and inflates prices for consumers across internet services and content delivery.

Media Industry: After mergers like Disney’s acquisition of 21st Century Fox, Disney, Comcast (NBCUniversal), Warner Bros. Discovery, ViacomCBS, and Sony dominate the global media landscape, controlling nearly 85% of film production and distribution.

Big Pharma & Greedy Healthcare

Just three companies (Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and Merck) control over 40% of the U.S. pharmaceutical market, allowing them to price-gouge life-saving medications. That means a customer in the U.S. pays 2 to 10 times more for the same drugs than other developed nations. The five largest pharmaceutical companies, Pfizer, Roche, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Novartis, control over 25% of the global drug market. For example, Pfizer alone controls 6.7% of the market. Consolidation in pharmaceuticals leads to less competition for essential drugs, contributing to skyrocketing drug prices and fewer incentives for innovation, especially in niche markets.

In 75% of U.S. states, the top two health insurers control more than half of the market, reducing competition and increasing premiums. In the 1980s, hospitals were largely independent or community-run. Today, four corporations (HCA Healthcare, CommonSpirit, Ascension, and Tenet) dominate the industry, leading to skyrocketing costs and declining care quality.

Big Tech

Big Tech firms Apple, Google (Alphabet), Amazon, Microsoft, and Facebook (Meta) collectively control over 90% of key technology sectors such as online advertising (Google and Facebook account for 60% of the market), cloud computing (Amazon AWS controls 34%, with Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud sharing another 30%), and smartphone operating systems (Android and iOS make up 99.9% of the global market). The dominance of Big Tech creates an environment where smaller companies find it nearly impossible to compete. These companies can buy out potential competitors or use their platforms to undercut competition, leading to monopolistic practices and fewer consumer choices.

Big Box & Online Retail

Amazon and Walmart dominate U.S. retail, with Amazon holding 47% of the e-commerce market, and Walmart holding around 10% of the total U.S. retail market. Combined, the five largest U.S. retailers of Amazon, Walmart, Costco, Home Depot, and Walgreens control nearly 60% of the U.S. retail market. These companies’ ability to leverage economies of scale, dictate terms to suppliers, and provide aggressive pricing drives smaller retailers out of the market. In particular, Amazon’s monopolistic hold on e-commerce stifles innovation and competition.

Never-ending Greed, History of Capitalism Repeats Itself

The influence of corporate greed extends beyond economic disparities, entrenching itself in the very mechanisms of our democracy through lobbying and the activities of special interest groups. These entities pour billions of dollars into the political system to shape legislation and regulation in their favor, often at the expense of public interest. The consequence is a political environment where Wall Street issues drown out Main Street concerns, as policymakers prioritize the agendas of their wealthiest constituents and corporate backers. This manipulation of the democratic process not only disenfranchises average Americans but also erodes trust in governmental institutions, threatening the foundational principles of transparency, accountability, and representation.

America’s economy has always swung between periods when private empires stitch markets into monopolies, and reform waves that break them back into the many. The first great consolidation of monopoly power, the Gilded Age, ended only after Congress passed legislation that protected the greater economic good. The Sherman Act of 1890 and the Supreme Court forced Standard Oil’s breakup in 1911, a defining moment that said bigness serving itself, not the public, must yield to competition. In the late New Deal, antitrust’s mission was reignited under Thurman Arnold, who used the law not just to punish cartels but to keep markets structurally open. The next major reset came in telecom: after years of litigation, AT&T divested its local phone monopoly in 1984, demonstrating that breakups could catalyze innovation, lower prices, and unleash adjacent industries.

So where are we in the cycle? Historically, America stiffens its antitrust spine only after concentrated power starts setting the rules for everyone else. By that measure, we have a long way to go for a corrective phase: liability findings and tougher merger guidance signal a turn, but the industrial structure still reflects decades of permissive consolidation.

The outcome will hinge on three levers: whether courts continue to accept broader theories of competitive harm embedded in the 2023 Guidelines; whether remedies (including structural ones) actually restore competitive conditions rather than merely police behavior; and whether enforcers can keep pace with serial acquisition strategies in fast-moving tech markets. If those levers pull in the public’s direction, we will start to bust monopoly power. If not, we risk headline victories for corporate America.

A Call to Action: Resist Corporate Greed

As we stand at this critical juncture, the need for decisive action has never been more urgent. It's time to dismantle the mechanisms that allow corporate greed to thrive at the expense of American workers and to reform a society that values dignity, equity, and the common good above profit. Together, we can reclaim the promise of America for every citizen, building a future where democracy flourishes in the service of the people, not the privileged few. The time for change is now, let us be the architects of a more just and equitable nation. To combat the insidious effects of corporate greed and wealth inequality, a multi-faceted approach is necessary:

Enact stringent campaign finance laws to limit the influence of money in politics, ensuring that elected officials serve the interests of their constituents, not corporate donors.

Implement and enforce robust regulatory measures that curb monopolistic practices, promote fair competition, and protect consumers and small businesses.

Adopt a progressive tax system where those at the top contribute their fair share, supporting public services and infrastructure that benefit all, not just a privileged few.

Force ethical business practices through transparency and accountability measures, holding corporations responsible for actions that undermine public welfare and economic stability.